L | ord Morpheus is dead. His death and burial played out in the hit comic book Sandman. The last issue, #75, came out just last month. In the wake of this final publication, Morpheus and his creator, Neil Gaiman, | |

have left behind a changed comics industry, one that is now open to a more

sophisticated breed of fantasy, and is another step further in its quest

to legitimize comics as an art form.

Sandman was the most successful recent entry in this struggle,

a subtle and intelligent contribution to an art form normally associated

with Spandex costumes and testosterone-laden fistfights. Although Sandman's

publisher, D.C. Comics, is better known for mainstay characters like Batman

and Superman, Sandman has been one of D.C.'s top sellers for years

now.

Sandman's success was not always so assured. In 1988, Gaiman

was asked if he wanted to write a regular series for D.C. Never a big fan

of the superhero genre, he suggested Sandman instead, and D.C.,

which has historically been more willing to explore fantasy than other

mainstream competitors, gave Gaiman the comic.

Sandman's creator, however, started with the impression that

the book would be a minor critical success, sell poorly, and then be canceled

after the first year. Karen Berger, who has edited the entire Sandman

run, agreed: "None of us knew at the time that the book would be what

it would be."

Who, after all, could have reasonably expected that a comic book as

thoughtful and well-read as Sandman would become the success it

became? What oracle would have told Gaiman that his comic, which refers

to Paradise Lost as effortlessly as to Little Nemo in Slumberland,

would earn him near-household-name status and a three-book, $1 million

advance deal with Avon Books?

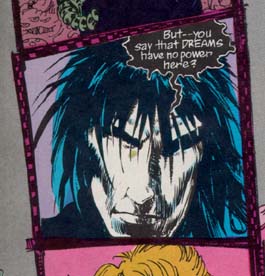

Sandman is a contemplative, heady book. It stars Morpheus, the

lord of all whimsy and imagination. In the stories, which range from the

fantastic to the horrific, Morpheus is sometimes at the forefront of the

action, and sometimes his powers and knowledge provide only a backdrop

for more intimate, mortal occurrences.

Sandman's succeeded, in part, because it appealed to the nontraditional

comic book audience; the focus on myth and history went against the mainstream

grain. Lance Smith, who works at the Dreamhaven comic shop in Dinkytown,

says that there have been a lot of readers who buy only Sandman

and no other comics.

In addition, Sandman attracted an unprecedented number of female

readers. On one hand, says Smith, the mere omission of the adolescent male

concerns in superhero books was enough to merit a look: " ... it's

not one continual fight scene, it's not a slugfest with Spandex."

On the other hand, Gaiman has a knack for well-rounded female characters:

"The women in Sandman may not always be sympathetic, but they're

strong and realistic. They have problems, but they're real problems, not

the kind of problems you see in X-Men."

Of course, the best way to appeal to readers of both genders is to simply

write well, which Gaiman does. In doing so, says Berger, he has highlighted

the importance of plot in what is often considered solely a visual medium:

"With Sandman, with most of the stuff he's done, he's really

helped raise the value of a writer in comics."

In mainstream comics, significant control over stories is rarely given

to the writer. Instead, the writer can be tightly constrained by the company,

which views its characters as valuable properties to be protected at all

costs. (Anyone who thought Superman was dead forever was fooling themselves.)

Gaiman's prestige as a writer gave him the leverage to buck this trend.

Not only has he been the sole author of Sandman (unusual for the

creators of comic book characters), but when he decided that the comic

would end at issue 75, D.C. had to concede, even though that meant the

end of a reliable and successful comic.

The idea of making a comic series finite is not entirely unheard of.

Most notably, Gaiman's friend, Dave Sim, has planned for years to end his

self-published comic Cerebus at issue 300, sometime in the next

millennium. The reason given by both is sensible enough: real stories don't

continue forever, outliving their originators as derivative, hackneyed

versions. Real stories work their way to an ending, and then they end.

That Gaiman would choose to end a comic of such fame was a public move

away from the product-driven mentality of mainstream comics. Instead, he

asserted what would have been obvious in almost any other medium: the author

makes or breaks a story, and without an individual vision, all the rest

-- setting, concept, character -- is just window dressing.

Beyond highlighting the importance of the individual author, the success

of Sandman paved the way for more sophisticated fantasy and horror

comics. Its success convinced D.C. to launch Vertigo, a new line of comics

whose titles have ranged from the gleefully vulgar Preacher to the

positively psychedelic Doom Patrol. Berger, who became the Vertigo

group editor, characterizes Vertigo books as "contemporary fiction

for adults in comic form."

Success also brought imitation from other companies, says Smith, citing

attempts by Marvel Comics, which is better known for their X-Men books,

to copy the Vertigo format. Their attempts included Razorline, based on

concepts by Clive Barker, and Marvel Edge, which Smith dismisses as "Vertigo

lite." "People look at Sandman and its success, get a

superficial view, mystical powers, etc., etc. They don't understand that

the writing behind Sandman is really good, and that's the important

thing, not the setting that the writing takes place in."

With Sandman finished, Smith predicts that he'll lose some customers,

but not too many. Bob Brynildson, who owns Source Comics and Games, isn't

too worried, either. "I don't think I'll sell less of a Vertigo comic

because Sandman is gone. If it happens, D.C. will redo Sandman

or do something similar to it."

If D.C. does try to somehow redo or copy Sandman, however, they

may have a difficult task ahead of them. "I can't think of a really

successful Sandman clone," says Smith. "I can think of

... a lot of good stuff that's come because Sandman and Vertigo

opened up some opportunities, but none obviously inspired by Sandman."

F | irst and foremost, Sandman is inimitable because inspiration is a difficult thing to copy. Gaiman's talent for characterization and plot -- whether put to use on family drama, fantasy | |

or horror -- is

what have drawn so many readers to Sandman.

In the first issues, Sandman runs at the same pace as many mainstream

comics: fast. But there are some individual issues that shine.

In the intimately terrifying "24 Hours," a madman uses one

of Dream's talismans to control and torment a diner's patrons. Gaiman creates

a handful of believable, sympathetic characters, and then tortures them

before our eyes.

The enchanting "Ramadan" tells the story of ancient Baghdad

and its king. The king realizes that, as with all great cities, the glory

of Baghdad is a fleeting one. So he sells the city to Morpheus, accepting

a fallen, dispirited Baghdad in its place, so that the true Baghdad may

continue to live in the dreams of others. The story behind "Ramadan"

is good, but what makes the issue remarkable is the florid, celebratory

art of P. Craig Russell, which does as much to convey the glory of the

once-great Baghdad as any of Gaiman's descriptions.

In comics, the interaction between artist and writer can take many forms.

Sometimes artist-writer teams establish themselves on one book, and sometimes

the artist and the writer are the same person. In the case of <I>Sandman</I>,

Gaiman has always been the driving force, with his writing being illustrated

by a constantly rotating staple of illustrators.

When it comes to good artists, Sandman has never been lacking.

Although Kelley Jones couldn't draw a relaxed facial expression if his

life depended on it, his stark, melodramatic linework is a nice complement

to Gaiman's otherworldly writing in Season of Mists. Shawn McManus

is a good match in A Game of You; his work is rounded, almost caricature-esque,

but subtle enough to convey a fine range of emotion and mood.

Unfortunately, Sandman goes through artists at a dizzying pace.

Few stories go by without a handful of artists tromping in and out of the

visual space Gaiman is working with; Season of Mists, for example,

credits seven artists for work on eight issues.

According to Berger, she and Gaiman had planned originally to have all

of the art done by only a few artists. However, theHowever, they soon encountered problems

with artists being able to keep to a monthly schedule, which led them to

the solution of spreading the work out among more than just two artists.

It's unfortunate that Berger and Gaiman couldn't have found another

way around the problem, whether by slave driving their artists or simply

slowing down their production schedule. When characters change appearance

abruptly between issues, or even in mid-issue, the effect is usually more

distracting than interesting.

The Kindly Ones, the second-to-last story which details the death

of Morpheus, offers a telling contrast. Marc Hempel drew almost every issue

of the work, and his gracefully simple art tilts between illustrative and

iconic, lending the epic tragedy a sense of timelessness.

In The Kindly Ones, Gaiman's writing, which had previously shown

the occasional, remarkable glimmer, begins to truly shine. Through a series

of machinations involving the Norse god Loki, the faerie Robin Goodfellow

and the witch Thessaly, the three Furies are set on Morpheus's trail. Weaving

together dozens of elements and characters from previous issues, Gaiman

and Hempel build a feeling of insistent dread and finality appropriate

to the death of Morpheus.

T |

he Kindly Ones isn't the only time that | |

As one of the Endless, Morpheus can appear as easily in Roman antiquity

as in modern-day Los Angeles. Given the historical and geographical scope

of the stories, it's amazing that any character shows up more than once.

But Gaiman's world is rich with coincidence. For example, Judy, a minor

character who dies in the same issue where she makes her first appearance,

haunts the rest of the book at the most unexpected times, when we learn

that she was best friends with Rose Walker (The Doll's House) and

a former lover of Foxglove (A Game of You). The Sandman world

may be infinite, but it seems to be populated by a finite community.

Although Gaiman's talent shouldn't be downplayed, it should be noted

that his breed of story owes some of its success to the mood of the times,

an environment where stories of coincidence and unseen powers fill a nagging

cultural need.

Clive Barker has written that there are two kinds of fantastic fiction:

"One ... offers up a reality that resembles our own, then postulates

a second invading reality, which has to be accomodated or exiled by the

status quo it is attempting to overtake ... The second kind of fantastique

is far more delirious. In these narratives, the whole world is haunted

and mysterious."

Describing a world that superficially resembles our own but is in fact

influenced secretly by the movements of inscrutable forces, Sandman

certainly qualifies as Barker's second breed of fantasy. But it's not alone

in this aspect. On one side, it is flanked by the growing success of television

shows such as The X-Files. On the other, it is flanked by the hit

role-playing game Vampire: The Masquerade, where vampires secretly

struggle for control over a mortal world that looks, at first glance, like

our own.

The renewed interest in these stories is an understandable reaction

to the chaotic meaninglessness implied by the modern condition. We are

bombarded with information but have few viable paradigms to process them.

We are becoming increasingly aware that the worst political problems require

solutions beyond the grasp of even the wisest leaders. And everywhere we

look, it becomes increasingly evident that everyone offering truth in any

form is also serving an agenda, which renders their truth suspect.

This kind of chaos heightens the need for myths, modern or otherwise.

As Ray Mescallado wrote in The Comics Journal in 1994: " ...

isn't mythology a way of arrogating control by humans, the claim of a greater

pattering instead of inchoate randomness, the illusion of human behavior

in the machinations of the unknowable?"

So at first, Sandman would seem to make sense of what may be

a fundamentally senseless existence, with gods defining and determining

the forces of nature and human existence.

Or does it? Gaiman's gods are not exactly gods in one crucial way: they

grow up. This isn't really surprising, given that Sandman is concerned

with gods more as personalities than as archetypes. Dream's relationships

with his siblings of the Endless -- Death, Desire, Despair, Delirium, Destruction

and Destiny -- resemble a dysfunctional family more than anything else.

But when we discover that Destruction has been a prodigal for over 300

years, leaving his role but not allowing anyone to fill it, it raises questions

about what the Endless truly are. After all, things have continued to burn

and collapse in his absence. So exactly what role do the Endless fulfill?

Or take the example of Lucifer, the former Lord of Hell. In Season

of Mists Lucifer tires of his position and abdicates, leaving Dream

the key to Hell. Gaiman takes a risk in deviating from myth so strongly:

If Lucifer chooses to abdicate, what are we to make of the meaning of Hell,

of damnation and of the devil as evil personified?

This kind of playing with myth is not unique. But if Gaiman's version

stands out, it's because he understands the source of a myth's strength.

It doesn't lie in legalistic interpretation, nor in revision of that interpretation.

It lies, instead, in the image itself, in the vision that lingers not as

a concept, but as a feeling.

In the wake of Lucifer's abdication, a throng of gods assemble in Dream's

palace, asking for the key to Hell. In a few short strokes, Gaiman fleshes

out his gods with a warmth and charm that a more theological treatment

would miss. The Egyptian goddess Bast is sultry, wise, and calculating.

The Norse god Loki is an emaciated, greedy trickster, as sly as he is immoral.

But to say that Gaiman simply understands myths would be an understatement

-- he obviously loves stories of all kinds. More than anything else, Sandman

is about the tale itself, about the power of imagining and the power of

telling.

In the World's End arc, travelers take refuge from a mysterious

storm at the World's End Inn to find themselves accompanied by others from

different times and different worlds. To pass the time, they spin yarns

of faerie adventures, encounters with sea serpents, and funereal apprenticeships

in the cities of the dead.

By themselves, most of the stories are remarkable, but Gaiman links

them together by focusing on the telling. In the World's End Inn, there

is a hearth, there is a table, and every traveler will leave enriched,

enlightened in some modest way by the tales of complete strangers.

It is the love of stories that drives Sandman's last issue, The

Tempest, which depicts Shakespeare's efforts to write his last play.

Dream provided Shakespeare with his talent, asking for two plays in return.

The first, A Midsummer Night's Dream was a gift for the faeries.

The second, The Tempest, in which the Duke Prospero manages to escape

his island exile through a mixture of fate and magic, is for Dream himself.

The creative, symbiotic relationship between Shakespeare and Dream is

ambiguous, and underlying it is the point that storytellers are magicians

as well, a thought echoed in Shakespeare's The Tempest: "These

our actors, as I foretold you, were all spirits, and are melted into air,

into thin air ..."

"The Tempest" is one last look at Morpheus as the Dream King,

driven by stories, composed of stories, bounded by stories. Near the end,

he tells Shakespeare, "I am Prince of Stories, Will, but I have no

story of my own. Nor shall I ever." Of course, he's wrong: He has

Gaiman as a reverent and perceptive scribe. Gaiman is reminding the reader,

on the eve of the Dream Lord's death, that a good tale never stops having

relevance, never stops being worth the telling. Princes may die, but they

will always live on in their stories.

[bio]